In the yard of his home just outside Boise, Idaho, Ely Bowman loves to toss balls and play with Bobo, the family Goldendoodle. He also loves the trampoline.

“If you were to come over and just watch him,” says his mother, Bekah, “you would not believe me if I told you he was blind.”

Ely, who turns 8 in July, lost his sight when he was 6 due to the rare neurological disorder CLN2 disease, one of the most common forms of a group of inherited disorders known as Batten disease.

Kids with CLN2 disease are missing an enzyme that chews up waste products in the brain. This lack of a cellular “Pac Man” to gobble up the bad stuff eventually leads to the destruction of neurons, resulting in blindness, loss of ability to speak or move, dementia, and death – usually by the teens.

There is no cure for CLN2 disease. But thanks to genetic scientists, neurosurgeons and nurses at CHOC, there is hope for delaying progression of the disease – one that claimed the life of Ely’s older brother, Titus, at age 6 in September 2016 before a cutting-edge therapy became available at CHOC six months later.

The therapy, Brineura, is a medication that treats the brain via a port under the scalp with a synthetic form of the missing enzyme. CLN2 patients come to CHOC every two weeks for the four-hour infusion to keep the drug working effectively.

Largest infusion center in country

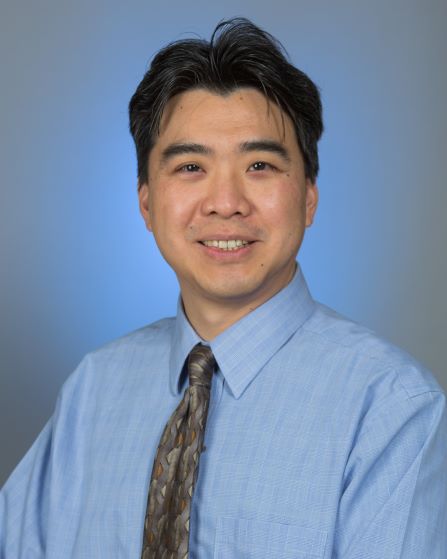

CHOC since has grown into the largest Brineura infusion center in the country and the second largest in the world. Kids from all over the United States have come to CHOC for Brineura treatment since it first was offered in March 2017 following a three-year effort by Dr. Raymond Wang to get the green light for CHOC to become the second infusion site in the U.S.

“When a family has a child with a rare disease,” Dr. Wang says, “and if the South Pole were the only place that was offering treatment, the family would find a way to get there. Those are the lengths that a rare disease family would go to help their child.”

CHOC now has treated 13 Brineura patients, the latest being 3-year-old Max Burnham, whose parents having been making the trek to Orange every two weeks from their home in the Bay Area since Max’s first infusion on Feb. 8, 2021.

3-year-old Max Burnham, CHOCs newest Brineura patient

Max Burnham; his sister, Ella; and parents, Laura and Matthew

CHOC’s Brineura program underscores its growing reputation as a destination for kids with rare diseases.

Recently, CHOC specialists started treating a 3-month-old with Hurler syndrome, another serious and neurodegenerative condition. The family drove across the country because CHOC is the only site in the world that has a clinical trial of gene therapy for their son’s condition.

Because the family will be staying at CHOC for at least through April 2021, a team of three study coordinators — Nina Movsesyan, Harriet Chang, and Ingrid Channa – helped the family get settled in at an Airbnb in Irvine.

“Our case managers and financial coordinators were crucial in getting the infant’s weekly enzyme therapy approved within a week’s time, and our excellent nurse practitioner, Rebecca Sponberg, asked purchasing to procure the enzyme drug for the baby on two days’ notice,” notes Dr. Wang, a metabolic specialist and director of CHOC’s Campbell Foundation of Caring Multidisciplinary Lysosomal Storage Disorder Program.

Dr. Wang says CHOC became an active site for the RGX-111 gene therapy after treating a child from a family in Indio in 2019. Another 14-year-old girl from West Virginia has received the same treatment.

“All of these cases wouldn’t be possible without the awesome teamwork from team members, who all are dedicated to the mission of CHOC,” says Dr. Wang. “I think it’s pretty remarkable that people from all over the country are coming here for clinical care and research studies because of our expertise and what we offer them: hope for their beloved children.”

A true team effort

For the Brineura infusions, which are administered by pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Joffre Olaya, CHOC metabolic specialists work closely with providers in CHOC’s Neuroscience Institute.

Susan See is nurse manager of CHOC Hospital’s neuroscience unit, where the patients receive their infusion and stay for care afterward.

“We quickly put together a comprehensive program that really treats the patient and family not just medically, but also from an emotional support standpoint,” she says.

Batten disease especially is terribly cruel because its symptoms typically hit just as parents are starting to enjoy their child reaching several developmental and cognitive milestones such as walking and talking.

Untreated, the disease eventually takes all that away.

“What makes them who they are gets rapidly erased,” says Dr. Wang. “As a practitioner, it’s hard. I’m trying to imagine being in the shoes of a parent knowing this is going to happen to their child.”

For Bekah Bowman and her husband, Daniel, the diagnosis for Titus and, two months later, Ely, was like being on a high diving board and being shoved off and belly flopping into the water.

“We had to learn what little control we have in life,” Bekah says.

The Bowmans worked closely with Dr. Wang to get the Brineura clinical trial launched at CHOC.

“When we met Dr. Wang,” Bekah says, “he told us: ‘We don’t have the answers for you right now, but I want you to know we’re going to keep fighting and we’re not going to give up.’”

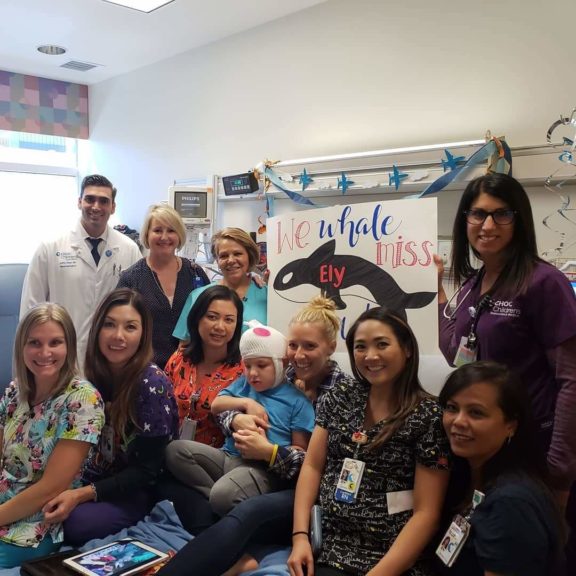

Brineura families form tight bonds with their team at CHOC, which includes eight nurses who have been trained to care for them: Allison Cubacub, Genevieve Romano-Valera, Anh Nguyen, Melissa Rodriguez, Kendall Galbraith, Annsue Truong, Monica Hernandez and Trisha Stockton.

Some families, including the Bowmans, have moved on from the program at CHOC when Brineura infusions became available near their hometowns. The Bowmans returned to their native Idaho outside Boise in October 2018. Leaving CHOC was difficult.

Ely Bowman remained a patient at CHOC until his family moved back to Idaho in 2018

Dr. Joffre Olaya (far left) and members of Ely Bowman’s CHOC team at Ely’s going-away party in October 2018

“That was one of the hardest goodbyes we had to say,” Bekah says.

All Brineura patients receive the transfusions on the same day – something unique to CHOC, See says.

“We learn what is unique about each patient and we become very close to them,” she adds. “It really reminds us why we said yes to nursing. What we thrive on is being able to care for families.”

Quick to action

Laura Millener, the mother of Max, CHOC’s latest Brineura patient, says she selected CHOC for Max’s condition, diagnosed in January 2021, because he needed to be treated right away. She first spoke to Dr. Wang on Jan. 11, and Max got his first infusion less than a month later.

“You could just tell how much he cares about his patients,” Laura says of Dr. Wang.

Says Dr. Wang, who has three children ages 10 to 18: “I count [my patients and my families] as my extended family, and I want the best for all of them.”

Laura and her husband, Matthew, a C-5 pilot in the U.S. Air Force, will be relocating to Quantico Marine Base in Virginia this summer from Pleasantville, Calif. Max, who has a 6-year-old sister, Ella, will continue his Brineura infusions at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

“I don’t want to leave CHOC,” Laura says. “CHOC has done such an amazing job of making this easier on us. I am so grateful for the team.”

Dr. Wang says the Brineura infusions have made it possible for the patients to maintain meaningful interactions with their parents and siblings – despite having such conditions as, in Ely’s case, blindness.

Ultimately, the goal is for CHOC to be considered for a gene therapy clinical trial aimed at giving brain cells the ability to produce the missing enzyme by itself so Batten disease patients wouldn’t have to receive infusions every two weeks. Dr. Wang says such a trial could happen this fall.

“If there’s anything in my power I can do to help these families,” says Dr. Wang, “I’m going to try to make it happen.”